[ad_1]

In a recent study, scientists found that a high-fat diet can damage the immune system and speed up tumor growth. In previous research, obesity increased the risk of more than 12 different cancers; it also led to a worse diagnosis and survival rate. This research also helped scientists learn how obesity increases tumor growth; underlying causes include metabolic changes and chronic inflammation. At Harvard study published on December 9, 2020, researchers found that obesity actually gives cancer cells the advantage over immune cells when they struggle for fuel.

Researchers at Harvard Medical School used mice to analyze how cancer cells would react to a high-fat diet. The study published in the journal Cell reveals new information on obesity and cancer. This new information could change the future of immunotherapy.

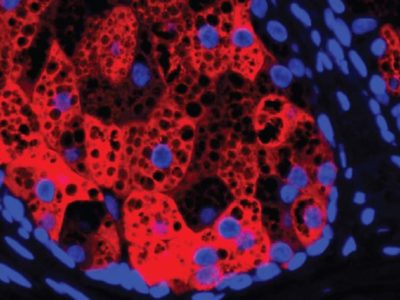

The team found that a high-fat diet reduces the number and antitumor activity of CD8 + T cells, an important immune cell, within tumors. The scientists found that this happens because cancer cells alter their metabolism in response to increased accessibility to fats. Therefore, they have a better ability to eat fat molecules, which deprives T cells of fuel, increasing tumor growth.

“Putting the same tumor in obese and non-obese settings reveals that cancer cells reconfigure their metabolism in response to a high-fat diet,” said Marcia Haigis, professor of cell biology at HMS ‘Blavatnik Institute and co-lead author of the study. “This finding suggests that a therapy that could potentially work in one setting might not be as effective in another, which must be better understood given the obesity epidemic in our society.”

Implications of this research for the future of immunotherapy

The research revealed that blocking the metabolic reprogramming process decreased tumor growth in mice given high-fat diets. In current immunotherapies, oncology nurses use CD8 + T cells as the primary strategy to stimulate the immune response against cancer. The new study may lead to better immunotherapy techniques in the future.

“Cancer immunotherapies are having a huge impact on the lives of patients, but they are not benefiting everyone,” said co-lead author Arlene Sharpe, HMS George Fabyan professor of comparative pathology and chair of the Blavatnik Institute’s Department of Immunology.

“We now know that there is a metabolic tug of war between T cells and tumor cells that changes with obesity,” Sharpe said. “Our study provides a roadmap for exploring this interaction, which may help us start to think about cancer immunotherapies and combination therapies in new ways.”

For the study, the team looked at how obesity affected various types of cancer in mice, including breast, melanoma and colorectal cancer. The researchers fed the mice normal or high-fat diets; the mice that consumed the most fat gained weight and experienced other signs of obesity. Next, they studied the various types of cells and molecules in and around tumors, known as the tumor microenvironment.

How Cancer Cells Reacted to Higher Fat Levels

As expected, the team found that tumor growth occurred more rapidly in mice on high-fat diets. However, they found that this only happened with immunogenic cancers, which have large numbers of immune cells. The immune system also recognizes them more easily, making them more likely to respond.

The study revealed that obesity-related tumor growth depended solely on the activity of CD8 + T cells; These immune cells attack and destroy cancer cells. The diet did not affect the rate of tumor growth if the researchers removed CD8 + T cells from the mice. Interestingly, they found that high-fat diets caused a decline in immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. However, the immune cells did not change in any other part of the body.

What the team discovered

Cells that remained in the tumor showed less force, divided more slowly, and became lethargic. However, when the researchers grew these cells in a laboratory, they showed normal activity levels. For the team, this implied that something in the tumor was causing the cells to malfunction.

Furthermore, the team found that in obese mice, the microenvironment lacked important free fatty acids, a key fuel for cells. The rest of the body still contained fatty acids, as is to be expected in obesity.

This led the researchers to keep track of the metabolic profiles of the various tumor cells for normal and high-fat diets. Their analysis found that cancer cells adapted their metabolism when faced with greater accessibility to fats. When placed on a high-fat diet, cancer cells alter their metabolism to increase fat absorption. The immune cells did not reprogram themselves, causing the cells to run out of essential fatty acids.

“The paradoxical depletion of fatty acids was one of the most surprising findings of this study. It really amazed us and was the launching pad for our analyzes, ”said Ringel, a postdoctoral fellow in Haigis’ lab. “That obesity and whole body metabolism can change the way fuel is used by different tumor cells was an exciting discovery, and our metabolic atlas now allows us to better analyze and understand these processes.”

Final thoughts on changes in cancer metabolic pathways and immune cells

The team used single-cell gene expression analysis, comprehensive protein studies, and high-resolution imaging to study how various diets alter metabolism. By analyzing these cells in the microenvironment, they focused on a protein called PHD3. This protein slows down the absorption of fat in normal cells. However, cancer cells in obese mice had lower levels of PHD3 compared to healthy mice.

When the team increased the PHD in the cells, they found that the tumor’s fat intake dropped dramatically. This also helped the free fatty acids to recover in the tumor microenvironment. Therefore, increasing PHD3 expression reversed most of the negative results of a high-fat diet on immune cell function. Tumor growth The rate with high levels of this protein decreased in obese mice compared to those with low PHD3. The increased activity of immune cells caused this to occur; in obese mice without immune cells, protein levels did not affect tumor growth.

While PHD3’s potential in treating cancer will require more research, this discovery may lead scientists to focus more on cellular metabolism in the future.

“We are interested in identifying pathways that we can use as potential targets to prevent cancer growth and increase antitumor immune function,” Haigis said. “Our study provides a high-resolution metabolic atlas to obtain information on obesity, tumor immunity and crosstalk, and competition between immune and tumor cells. There are likely many other cell types involved and many more avenues to explore. “

[ad_2]

Original source