Concurrent training is the technical term for including both cardio and strength training in your workout routine.

Generally, the goal is to get better at both types of training simultaneously. That is, you’re trying to gain muscle and strength by lifting weights and improve your endurance by going faster and/or further in your cardio workouts.

If you’ve spent any time in the fitness space, though, you know that many people claim this is a fool’s errand.

These people argue that you can’t effectively adapt to both cardio and strength training at the same time. Instead of improving at both—getting bigger, stronger, and fitter—you just end up being mediocre across the board. In other words, they claim concurrent training turns you into a jack of all trades and a master of none.

While there’s a kernel of truth to this idea, scientific research shows it’s more wrong than right. In fact, a growing body of evidence suggests that if you want to get bigger, stronger, leaner, and fitter, combining cardio and strength training is actually better than just lifting weights.

To get these benefits, though, you have to implement concurrent training correctly. Do it wrong, and you’ll banjax your ability to gain strength and muscle and increase your risk of injury. Do it right, though, and you can enjoy the benefits of cardio and strength training scot-free.

The Wrong Way to Combine Cardio and Strength Training

Concurrent training naysayers are right that combining cardio and strength training can hamper your ability to gain strength and muscle, a phenomenon known as the interference effect.

One of the first and best examples of this comes from a study conducted in 1980 at the University of Washington by Robert C. Hickson. Hickson was a researcher and recreational runner and powerlifter, and he noticed that his two hobbies seemed to be conflicting with one another. Thus, he created a study to measure this “interference effect.”

In the study, he had 23 healthy, active men and women in their mid-twenties do one of three workout routines for 10 weeks:

- Strength training alone, which consisted of five intense lower body workouts per week.

- Cardio alone, which consisted of six intense running and cycling workouts per week (cycling intervals and continuous runs).

- Strength training and cardio, which combined the two programs (11 workouts per week), often with both cardio and strength training occurring on the same days.

Hickson found that the people who combined strength training and cardio gained just as much muscle as the people who only did strength training, but gained significantly less strength. What’s more, they also improved their endurance just as much as the people who only did endurance training.

In other words, adding cardio to strength training slightly decreased the participants’ ability to gain strength and had little to no impact on their ability to gain muscle, and strength training didn’t interfere with the benefits of cardio at all.

Since Hickson’s seminal study on this topic, many other scientists have found evidence of the interference effect. In most of these studies, cardio reduces strength gain significantly and sometimes reduces muscle gain, whereas strength training doesn’t seem to blunt the benefits of cardio.

There’s a major problem with these studies, though:

Most of them are designed to elicit the interference effect. That is, the goal isn’t necessarily to discover how to optimally combine cardio and strength training. Instead, it’s to create a training program that’s all but guaranteed to cause interference so the researchers can observe and analyze it.

Hickson’s original study is a perfect example of this. The participants were doing heavy lower-body strength workouts five times per week, which is a long row to hoe by itself. Then, on top of their weightlifting, they started doing almost four hours of intense running and cycling each week, which is just cruel and unusual.

Despite this grueling workout routine, these people still gained almost exactly the same amount of muscle as the people who only lifted weights. They also lost 2% body fat, whereas the people who just lifted weights didn’t lose any. This also means that the people doing concurrent training were probably in a calorie deficit, which could also partly explain why they gained less strength.

The bottom line is that Hickson’s study and many like it went a long way in helping identify and quantify the interference effect, but used totally unrealistic and suboptimal training methods.

The Right Way to Combine Cardio and Strength Training

Many fitness gurus point to studies like those by Hickson as evidence that concurrent training is always a sisyphean slog.

What they fail to mention, though, is that many studies have shown no evidence of any interference effect and some have shown that cardio can enhance muscle growth when added to a strength training program.

For example, multiple studies have shown that combining cycling and strength training actually results in more muscle growth (and sometimes strength) than strength training alone. In one study, people who did both cycling, leg presses, and leg extensions increased their quad thickness twice as much as people who only lifted weights. In untrained people, cycling can even cause muscle growth by itself.

In fact, one of the largest and most thorough reviews conducted on concurrent training concluded that “there are as many papers reporting a greater increase in muscle hypertrophy with concurrent training as there are papers showing an interference effect.” Even in studies where the interference effect has occurred, it’s never completely stopped muscle growth or strength gain, but only slowed it.

Why the conflicting results? Why does cardio seem to check strength and muscle gain in some studies and accelerate it in others?

The answer has to do with how you combine strength training and cardio in your workout routine. In other words, the devil is in the details.

The main factors that influence how much cardio interferes (or doesn’t interfere) with strength training are:

- The type of cardio you do

- When you do your cardio and strength training workouts

- How much cardio you do

- The intensity of your cardio workouts

- How much you eat

First and foremost, running causes much more fatigue and muscle damage per unit of time than cycling, rowing, skiing, and other lower-impact forms of cardio. Thus, studies that combine lots of running with strength training, like Hickson’s study, tend to show a much greater interference effect than those that use cycling, rowing, cross-country skiing, and similar kinds of low-impact cardio.

Most research also shows that the interference effect is muscle-specific. That is, lots of running won’t directly interfere with your ability to improve your bench press, but it could interfere with your ability to strengthen and grow your legs.

That said, lower body cardio can still interfere with your upper body weightlifting if you do enough to cause substantial whole-body fatigue, but you can largely mitigate this problem with proper workout programming.

For instance, if you’re doing cardio and strength training for the same body part (e.g. running and squats), simply doing these workouts on separate days reduces the interference effect to almost nothing. And if you do them on the same day, you can largely mitigate the interference effect by eating plenty of carbs throughout the day (to restock glycogen levels) and separating your workouts by at least six hours.

If you absolutely must do both cardio and strength training in the same workout, doing your strength training first will also help minimize the interference effect.

The total amount of cardio you do per week also affects how much it interferes with your strength training. It’s impossible to pinpoint exactly how much cardio is too much, since this depends on the type of cardio you do and when you do it, but most people can do 3 to 6 hours or so of cardio per week before it begins to detract from your strength training. Additionally, the more intense your cardio workouts, the less volume you can do before it begins to sap your ability to gain strength and muscle.

Another major factor that impacts how well your body responds to concurrent training is your diet. Specifically, a calorie deficit hampers your ability to recover and build muscle, which can magnify the interference effect.

Cardio burns a lot of calories, and when weightlifters start doing cardio, they often don’t eat enough to make up for how many calories they’re burning. Thus, one of the reasons some people think cardio is hurting their gains isn’t necessarily due to the cardio, per se, but to unwittingly putting themselves into a calorie deficit.

So, what are the key takeaways from all of this? What’s the right way to combine cardio and strength training?

The main things to keep in mind are to:

- Choose cycling and other low-impact cardio instead of running.

- Keep most of your cardio workouts fairly short.

- Do most of your cardio workouts on separate days from your lower-body strength training workouts.

Stick to those three guidelines, and you can more or less completely eliminate the interference effect.

My Top 8 Tips for Concurrent Training

If you want to learn more about how to properly combine cardio and strength training to minimize the interference effect, follow these eight guidelines.

1: Prioritize low-impact forms of cardio like cycling, rowing, skiing, and rucking.

I can’t emphasize this enough: if you want to avoid the interference effect, be stingy with your running.

Anecdotally, I’ve found that most people can work up to about 2 to 3 hours of running per week before they start to drag anchor in their weightlifting workouts. When it comes to lower-impact forms of cardio like cycling, rowing, rucking, and skiing, though, most people can do twice as much cardio (~4 to 6 hours) before it begins to cause problems.

You can still combine running and strength training, but you should keep your running volume lower than if you were doing other forms of cardio.

2: Limit the volume and duration of your cardio workouts.

No matter what kind of cardio you do, if you do enough, it will eventually interfere with your strength training workouts.

If you just want to stay lean and fit, a good rule of thumb is to limit the time you spend doing cardio to no more than half the amount of time you spend weightlifting each week. If you lift weights for four hours per week, don’t do more than two hours of cardio per week. In general, it’s also best to limit most of your cardio workouts to 30 to 60 minutes or less.

If you really enjoy cardio or compete in an endurance sport, how much cardio you should do depends on your ambitions (completing vs competing) and how your body responds to your training. That said, here are some general guidelines that have worked well for me:

- Limit your total weekly cardio volume to 4 to 6 hours per week, with no more than 2 to 3 hours of this being running (and ideally, even less).

- Limit the duration of most of your cardio workouts to less than 60 minutes, with only one or two workouts lasting longer than this per week.

- Only break these rules in the weeks or months leading up to a specific competition or challenge, in which case you’ll likely want to do more cardio to burnish your endurance.

3: Separate your cardio and strength training workouts by as much time as possible.

As a general rule, you want to allow as much time between cardio and strength training workouts as possible. The most obvious way to do this is to simply stagger your workouts throughout the week (cardio one day, strength training the next), but this severely limits how often you can train.

Thus, most people find it necessary to do at least some cardio and strength workouts on the same day. In this case, it’s best to separate your workouts by at least 6 hours, ideally doing your strength training workouts earlier in the day and your cardio workouts later. For example, you could do your strength training in the morning or mid-day, and your cardio workouts in the afternoon or evening.

There are some exceptions to this rule, such as high-intensity cycling and squats (which you can often do on the same day, as they have a similar physiological effect on the body). As a general rule, though, the more time between cardio and strength training, the less the interference effect will rear its head.

If you must combine cardio and strength training in the same workout, do your strength training first.

4: Emphasize either strength and muscle gain or endurance.

While you can improve your endurance and gain muscle and strength at the same time, you can’t maximize your progress in both directions simultaneously. In other words, it’s still smart to emphasize cardio or strength training at any one time.

And if your main goal is to gain muscle and strength and get or stay lean, the winning formula is to prioritize strength training and “fit in” cardio around your weightlifting in a way that minimizes the interference effect. This means following a well-designed strength training program that includes progressive overload.

If you’re a hardcore endurance athlete or want to complete some kind of endurance event (marathon, gran fondo, backpacking trip, etc.), you’ll need to temporarily deemphasize strength training while you put more energy into cardio.

5: Gradually increase the volume of your cardio workouts.

One thing that cardio and weightlifting have in common is if you want to get better, you have to make your workouts more challenging over time.

You have to walk a tightrope, though, because if you push yourself too hard, too soon, you’ll likely give yourself a repetitive stress injury (RSI). While many people are wary of running injuries, low-impact forms of cardio like cycling, rowing, and even walking can cause serious hip, knee, and ankle pain that can dog you for months.

The best way to avoid this problem is to only do low-intensity workouts (no HIIT, sprints, circuits, etc.) of 60 minutes or less for your first month of concurrent training. After this initial “warm up” period, increase your total weekly cardio volume by no more than 10% per week. For instance, if you do 2 hours of cardio one week, do no more than ~2 hours and 10 minutes the next week, and so on.

6: Emphasize lower intensity cardio over high-intensity interval training.

Many people believe that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) interferes with strength training less than low-intensity steady state cardio (LISS), but this is usually not the case.

HIIT causes a larger decrease in strength than lower intensity cardio, requires more mental energy to complete, and causes more muscle damage (especially in the case of running) than lower-intensity cardio. Some research also shows HIIT may decrease hypertrophy more than LISS.

That said, HIIT also has its merits. It’s a very efficient way to burn a lot of calories in a short period of time, it keeps your cardio workouts interesting, and it offers some health and fitness benefits you can’t get from low-intensity cardio.

Thus, I recommend you do no more than one HIIT workout per week, and do the rest of your cardio workouts as LISS.

7: Avoid muscle failure in your strength training and exhaustion in your cardio workouts.

Taking your sets to failure during your weightlifting workouts doesn’t cause more muscle and strength gain than taking your sets two to three reps short of failure, but it does produce significantly more fatigue.

The same thing is true of exhausting cardio workouts—you don’t need to push yourself to the end of your tether to improve your fitness. Instead, you should finish most of your workouts with a little gas left in the tank. The only time you should really push yourself to your limits are when you’re trying to set a new one-rep max for a weightlifting exercise or a personal record for your cardio, which should only occur every few months.

This conservative approach ensures that your body can effectively recover from your training, which will produce better results over time than going balls to the wall too often.

8: Deload every 3 to 6 weeks on average.

Concurrent training is more taxing than only doing strength training or cardio, which is why you need to be particularly careful about getting enough rest. One of the best ways to do this is to deload regularly, which involves reducing the volume and/or intensity of your workouts to give your body time to recover before another few weeks of hard training.

In general, I recommend you deload both your strength training workouts and cardio workouts during the same week. This keeps things simple from a scheduling standpoint and ensures you don’t push too hard in the workouts you aren’t deloading, which would negate the benefits of the deload. (For example, pushing harder in your strength workouts while you deload your cardio workouts).

In terms of how you deload, here’s what I recommend:

- For your strength training workouts, reduce your number of sets and reps by half, but keep using the same weights as you were the week before the deload.

- For your cardio workouts, cut your volume in half but keep your intensity the same. If you’re feeling particularly frazzled, you can also do all of your cardio at a low intensity during your deload.

Cardio and Strength Training Routine

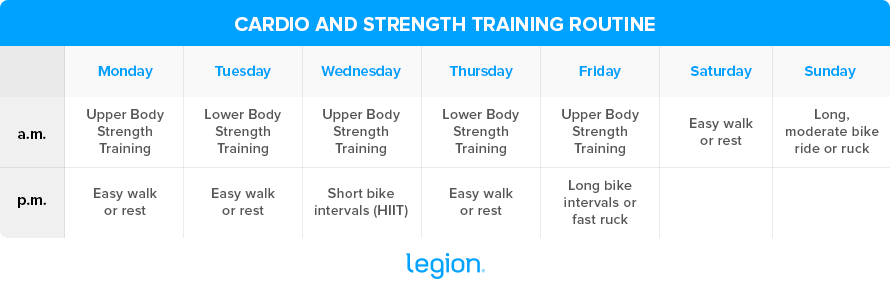

This is a typical concurrent training routine that involves five strength training workouts and three cardio workouts (along with several optional walks).

You can combine cardio with any strength training routine, but upper/lower and push pull legs splits make it easy to schedule your cardio workouts on days you aren’t training legs.

I’ve used cycling and rucking for the cardio workouts in this sample routine, but you can also do rowing, skiing, swimming, Nordic track, elliptical, or running for your cardio (just keep the guidelines you learned earlier in mind). This routine is set up so that on days that you do both cardio and strength training, you lift weights in the morning and do cardio in the afternoon or evening. On days you don’t lift weights, you can do cardio any time you like.

What are your thoughts on combining cardio and strength training? Let me know in the comments below!

+ Scientific References

- Carroll, K., Bazyler, C., Bernards, J., Taber, C., Stuart, C., DeWeese, B., Sato, K., & Stone, M. (2019). Skeletal Muscle Fiber Adaptations Following Resistance Training Using Repetition Maximums or Relative Intensity. Sports, 7(7), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7070169

- Fyfe, J. J., Bishop, D. J., & Stepto, N. K. (2014). Interference between concurrent resistance and endurance exercise: Molecular bases and the role of individual training variables. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 44, Issue 6, pp. 743–762). Adis International Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0162-1

- Sabag, A., Najafi, A., Michael, S., Esgin, T., Halaki, M., & Hackett, D. (2018). The compatibility of concurrent high intensity interval training and resistance training for muscular strength and hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(21), 2472–2483. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1464636

- Clarsen, B., Krosshaug, T., & Bahr, R. (2010). Overuse injuries in professional road cyclists. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(12), 2494–2501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546510376816

- Areta, J. L., Burke, L. M., Camera, D. M., West, D. W. D., Crawshay, S., Moore, D. R., Stellingwerff, T., Phillips, S. M., Hawley, J. A., & Coffey, V. G. (2014). Reduced resting skeletal muscle protein synthesis is rescued by resistance exercise and protein ingestion following short-term energy deficit. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism, 306(8). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00590.2013

- Coffey, V. G., & Hawley, J. A. (2017). Concurrent exercise training: do opposites distract? In Journal of Physiology (Vol. 595, Issue 9, pp. 2883–2896). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP272270

- Häkkinen, K., Alen, M., Kraemer, W. J., Gorostiaga, E., Izquierdo, M., Rusko, H., Mikkola, J., Häkkinen, A., Valkeinen, H., Kaarakainen, E., Romu, S., Erola, V., Ahtiainen, J., & Paavolainen, L. (2003). Neuromuscular adaptations during concurrent strength and endurance training versus strength training. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 89(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-002-0751-9

- Murach, K. A., & Bagley, J. R. (2016). Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy with Concurrent Exercise Training: Contrary Evidence for an Interference Effect. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 46, Issue 8, pp. 1029–1039). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0496-y

- D G Sale, I Jacobs, J D MacDougall, & S Garner. (n.d.). Comparison of two regimens of concurrent strength and endurance training – PubMed. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2381303/

- Bruce Craig, Jeff Lucas, Roberta Pohlman, & Herbert Stelling. (n.d.). The Effects of Running, Weightlifting and a Combination of Both on Growth Hormone Release. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://insights.ovid.com/strength-conditioning-research/jscr/1991/11/000/effects-running-weightlifting-combination-growth/5/00124278

- Wilson, J. M., Marin, P. J., Rhea, M. R., Wilson, S. M. C., Loenneke, J. P., & Anderson, J. C. (2012). Concurrent training: A meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(8), 2293–2307. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3e2d

- Millet, G. Y., & Lepers, R. (2004). Alterations of Neuromuscular Function after Prolonged Running, Cycling and Skiing Exercises. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 34, Issue 2, pp. 105–116). Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200434020-00004

- Moritz Schumann, & Bent R. Rønnestad. (2019). Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training. In Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75547-2

- Konopka, A. R., & Harber, M. P. (2014). Skeletal muscle hypertrophy after aerobic exercise training. In Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews (Vol. 42, Issue 2, pp. 53–61). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000007

- Mikkola, J., Rusko, H., Izquierdo, M., Gorostiaga, E. M., & Häkkinen, K. (2012). Neuromuscular and cardiovascular adaptations during concurrent strength and endurance training in untrained men. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 33(9), 702–710. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1295475

- Lundberg, T. R., Fernandez-Gonzalo, R., Gustafsson, T., & Tesch, P. A. (2013). Aerobic exercise does not compromise muscle hypertrophy response to short-term resistance training. Journal of Applied Physiology, 114(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01013.2012

- Doma, K., & Deakin, G. B. (2014). The acute effects intensity and volume of strength training on running performance. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(2), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.726653

- Kikuchi, N., Yoshida, S., Okuyama, M., & Nakazato, K. (2016). The Effect of High-Intensity Interval Cycling Sprints Subsequent to Arm-Curl Exercise on Upper-Body Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(8), 2318–2323. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001315

- Hickson, R. C. (1980). Interference of strength development by simultaneously training for strength and endurance. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology, 45(2–3), 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00421333

If you enjoyed this article, get weekly updates. It’s free.

Sending…

Great! You’re subscribed.

100% Privacy. We don’t rent or share our email lists.